The most famous “secret society” was discovered in Taiwan in the 18th century. It was probably born as a group saving funds for weddings and funerals.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 6. Read article 1.

Chinese and Western historians agree that “secret societies,” and the Tiandihui in particular, belong to or represent the evolution of a type of “fraternal society” that was present in China from at least the 7th century CE. These societies, under the names “hui” and “she,” had a significant importance in the villages, and were recognized there as a quite legitimate part of the social organization.

If in the Middle Ages one often finds religious societies, from the 16th century onwards the most important village societies dealt with funerals. As funerals were quite expensive, the members of these “funeral societies” (already existing in the 7th century) paid a contribution to a common fund, which was then used to pay for the funeral expenses of each member at his death.

Less widely spread, marriage societies had a similar function. The common element, whether for funerals or marriages, was the constitution of a common fund, which allowed the constitution of “yinqian yaohui,” or mutual credit societies. They were important among the Chinese peasantry from the 18th century onwards.

All these societies almost always also had a ritual and religious function, in a culture where separating religion and society was never easy. All this remained within the traditional village organization. Even if the imperial authority was sometimes concerned about the excessive expenditure of the peasants for these societies, they remained within the social structure of the village and did not challenge the authorities.

The “secret societies” of the 18th century, on the other hand, were almost immediately considered as something dangerous and at risk of challenging the village social order. To them was attributed, wrongly or sometimes rightly, the practice of a “blood oath” or “blood initiation,” i.e., an oath consecrated by the sacrifice of an animal whose blood was then drunk. The practice was known in China in previous centuries, but was more often associated with insurrectionary political movements or criminal or pirate gangs, rather than with peaceful peasant associations.

What had happened? According to several historians, in the 18th century a situation similar to that of 19th-century America occurred in China. New forms of economy and the colonization of new lands in southeastern China, and even more so in Taiwan, produced a “frontier culture” and even a “bachelor culture.” They were mostly young males embarking on the often-dangerous adventure of emigration, followed by very few women.

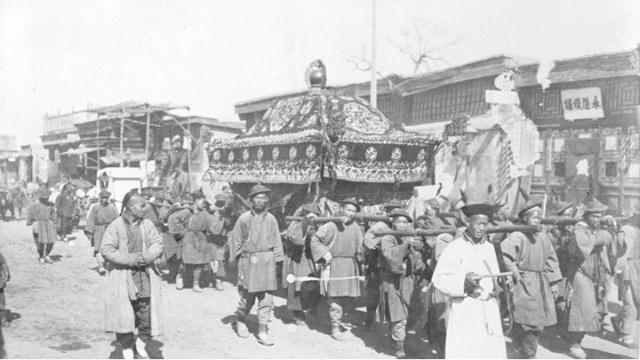

The authorities had great difficulty enforcing the law in this “frontier,” especially in Taiwan, and revolts were very frequent. It was during one of these, the Lin Shuangwen revolt (1787–1788), that the Qing imperial authorities “discovered” Tiandihui as a major problem.

Their investigation of the revolt demonstrated that Lin Shuangwen was a member of this society, which had been imported to Taiwan by a cloth peddler from the Fujian region called Yan Yan.

In Taiwan, the Tiandihui, which Yan Yan presented as a society that dealt with funerals and weddings, also protected its members in a dangerous environment, without neglecting petty crime activities. It had found fertile ground among people already involved in vendettas between families and between immigrants from different regions.

A branch of the Tiandihui had apparently taken root in 1786 under the name of “Society for the Advancement of Younger Brothers,” based on local questions about the rights of younger brothers denied by the elder brothers, a frequent problem in China at that time.

The Qing authorities’ harsh investigation persuaded them that the Tiandihui had not been born during Lin Shuangwen’s revolt. The members they had arrested told the police some rather bizarre stories about a society that would have been born in 1761 in Gaoqi (Fujian) among a group of former Fujianese emigrants in Sichuan who had returned to their country of origin, led by a monk called Wan Tixi.

While there are historians who believe that this Wan Tixi was a historical figure, it is less clear whether the leaders of other 18th-century anti-imperial revolts, such as Lu Mao and Li Amin, were also among the original members of the Tiandihui.

Lin Shuangwen’s revolt was not political only. The desire of local criminals not to be disturbed by the authorities also played a significant role. The Qing authorities launched a massive and fierce repression, which in fact favored the spread of the Tiandihui outside the Southeast and Taiwan, throughout China and in the Chinese colonies of Southeast Asia, where many persecuted members sought refuge.

It is in these times that Tiandihui members also took the name Hong, “red,” a common Chinese surname and reference to a sacred color.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.