The “Satanic panic” of the 1990s denounced imaginary crimes. Real crimes, however, are occasionally committed, by both Satanists and anti-Satanists.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 6 of 6. Article 5 of 6. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, article 4, and article 5.

To understand how an opposition to Satanism so strong to be called a “Satanic panic” grew in the late 20th century, we should go back to the murders of the Manson family. Most scholars who have studied the case now agree that the “Satanic” elements of his “family” were largely introduced by a jailed Manson intent on reinventing himself as a more important character than he actually was. In turn, Manson’s Satanic antics were readily used by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi (1933–2015) to build a major political (and later literary) reputation for himself.

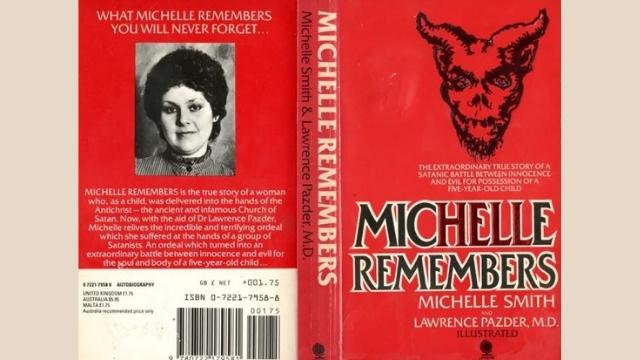

The Manson case, however, persuaded the American public that Satanists were not harmless eccentrics but were somewhat connected to violence and murder. The result was the largest wave of anti-Satanism in modern history, which ran from 1980 to 1990. Included in this wave were psychiatrists and psychologists, who believed the factual reality of the accounts of their patients (called “survivors”) who, under hypnosis, recalled experiences of Satanic violence (usually sexual) when they were children.

The same accounts, which would suggest the existence of a vast network of Satanic ritual abuse, perpetrated mostly on children, by clandestine and unsuspected Satanist organization, also found believers among fundamentalist Protestants and social workers. However, reports of the existence of “Satanic ritual abuse,” which came from “recovered memories” on the psychotherapist’s couch after many years, or from uncertain testimonies of children more or less “instructed” by social workers, were greeted with increasing skepticism, particularly after sensational trials had concluded with the alleged “Satanist ritual abusers” being declared not guilty.

In 1994, two official reports, one British, commissioned by the government from anthropologist Jean La Fontaine, and one from the U.S. National Center of Child Abuse and Neglect, dealt a fatal blow to the credibility of “Satanic ritual abuse” theories. According to the U.S. report, out of twelve thousand reports of alleged Satanic ritual abuse not a single case could be supported by evidence, although in a small number of cases individual pedophiles or couples (but not organizations) used Satanic paraphernalia to frighten their victims. The British report castigated the credulity of social workers and suggested measures to reduce their influence.

Although a few cases keep occurring in several countries to this very day, the wave of anti-Satanism of the early 1990s seems to have ceased toward the end of the decade. Thousands of men and women had been denounced, and in some cases prosecuted for crimes they had never committed. Thousands of lives and careers had been destroyed. In the end, cooler tempers somewhat prevailed, although there are still true believers in “recovered memories” and myths about “Satanic ritual abuse.”

Exaggerations are also fueled by folk statistics. One must beware here, in particular, of taking at face value the statistics provided by some of the more “public” Satanist organizations, which sometimes refer to address books where even the merely curious who have merely sent a letter of inquiry to the movement are registered, and not to actual “members.” Estimates circulated by anti-cultists and police organs sometimes rubric among Satanists, improperly, all Black Metal concert-goers. “Organized” Satanists are probably in the thousands in the world, not in the tens of thousands.

There are also young self-styled Satanists who adopt a “Satanic” lifestyle derived from music and movies and sometimes perform rituals they have found on the Internet or in some book. Police officers in some countries call them “acid” Satanists because of their liberal use of recreational drugs.

The youth groups of “acid” Satanism are much more difficult to identify and count, and sometimes more dangerous: not so much because of greater inherent violence but because of less possibility of surveillance by law enforcement authorities. The crimes they may commit include animal sacrifices, and desecration of churches and (more often) cemeteries. In youth groups, it is more likely that the sense of the boundary between metaphor and reality is lost, which may lead to serious crimes such as rape, and in very rare cases even murder.

In Chiavenna, Italy, in 2000, three girls brutally murdered a nun, Sister Maria Laura Mainetti (1939–2000), beatified by the Catholic Church in 2021. The girls wrote in their journals sentences glorifying Satanism, but it came out at their trial that they had never had any contact with Satanist groups, and dreamed, vaguely, of establishing one of their own.

Another case of criminal Satanism in Italy concerned the Beasts of Satan, a group formed in connection with a Death Metal band. Its members were arrested in 2004 and sentenced in 2005 for three “ritual” murders and for having induced another young man in the group to commit suicide. Their case is more similar to the Metal-connected Scandinavian homicides discussed in the previous article of this series.

Is Satanism dangerous? Most Satanist groups, and most Extreme Metal bands that celebrate Satan in their lyrics, have never been accused of crimes. At the fringe of Metal music, and in certain “acid” juvenile groups, serious crimes have been committed, including murder, allegedly in the name of Satan and Satanism, although sometimes the Satanic references hide different motivations such as drug dealings gone sour or personal vendettas.

Crimes have also been committed in the name of anti-Satanism, particularly slander and false accusations, which in several countries in the years of the Satanic panics and beyond have led innocents to jail and caused a significant amount of unnecessary suffering.

Conspiracy theories are also dangerous, as proven by the American hysteria, fueled by QAnon and other extremist outlets, about imaginary Satanic crimes of pedophile ritual abuse, in which leaders of the Democrat Party were accused of being involved. On December 4, 2016, a man arrived with a rifle at Comet Ping Pong in Washington DC, a pizzeria where children were allegedly abused by Democrat Party politicians in Satanic rituals, and started shooting. Happily, the police arrested him before anybody was injured.

Law enforcement’s surveillance of both Satanist groups that see violence and even murder as legitimate tools for worshiping Satan, and anti-Satanist conspiracy theorists who threaten retaliation against imaginary Satanists, is fully justified. In democratic countries, such surveillance activities should always respect the principle that ideas, no matter how unpalatable they may appear to many, cannot be prohibited, unless they explicitly incite to illegal forms of discrimination or to violence.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.