An outspoken and controversial conservative Catholic, the Ukrainian Canadian artist picked up some memorable fights for freedom of religion.

by Massimo Introvigne

Almost unknown in continental Europe, but admired throughout the Anglo-Saxon world, William Kurelek is considered by many in Canada as one of the country’s most significant artists, although he has also been both criticized and censored for his conservative approach to moral issues.

During his lifetime, Kurelek believed that religious liberty was denied in the country of his parents, Ukraine, which was part of the Soviet Union, and at risk also in the West. While others may object that Kurelek’s aggressive promotion of his religion-based points of view on controversial matters was the reason for some censorship of his work, his supporters would counter that through deliberately provocative paintings the artist was in fact submitting the idea that religious liberty reigned in Canada to a crash test of sort.

A “painter of the people,” Kurelek was especially loved because he painted Canada—the country of minorities par excellence—province by province, and minority by minority. Always starting with meticulous research, travels across the nation, and the study of old photographs, he reconstructed in a series of famous cycles the lives of the pioneers of the great prairies, of French-speaking Catholics, of Ukrainians like himself (they represent the fourth ethno-linguistic group in Canada), of Poles, of Jews.

Kurelek devoted his life to criticizing the concept of art for art’s sake. For him, art has two functions: historical, to preserve memories that modernity threatens to destroy; and pedagogical, to call us to reflect on the great questions of human life and the evils of our time. Ultimately, he offered to these questions answers deeply rooted in religion.

William Kurelek was born on March 3, 1927, on a farm near Whitford in the province of Alberta. His parents, Orthodox Christians, were immigrants from Ukraine. Life on the prairie was hard as the Great Depression, a series of fires, and a grasshopper invasion put a strain on the Ukrainians of Alberta and Manitoba. Somehow, William’s parents thought God had abandoned them. When their house burned down in one of the great fires of the era, icons disappeared from the new home. Young William thus grew up without a religious education. He will criticize his parents for this only several years later, but the conflict with his father was nonetheless very harsh.

A solid farmer, Kurelek senior reproached his son for his lack of interest in practical matters. Instead of excelling in the work in the fields or in sport like other young Ukrainians in the area, William was a shy boy who picked up a pencil and paper as soon as he could, and began to draw. At least he was good at school, and when the family moved to another farm in Manitoba, in Stonewall, they sent him to study in the provincial capital, Winnipeg, first at the prestigious Newton High School and then at the University of Manitoba.

But he did not accept his parents’ help, and preferred to pay for his studies by working in the holidays as a lumberjack, despite a frailty that made him avoid military service and the war. The family would like to make him a doctor or a lawyer, but William, after graduating in 1949, could not resist his artistic vocation and transferred to the prestigious Ontario College of Art.

The conflict with the family continued to be devastating for William. It caused him psychiatric problems, an inability to approach women that he would overcome only after his religious conversion (he will marry in 1962), and an addiction to drugs originally taken for a thyroid problem.

He left the Ontario College of Art and, like many American artists, went to Mexico where there was a flourishing anglophone artistic-literary colony. In 1952 he left for London, where he perfected his technique, and created the first paintings that would later be recognized as masterpieces. He was also admitted to the Maudsley Psychiatric Hospital, then at the forefront of therapies based on artistic expression. Here he became particularly close to a therapist, Margaret Smith, who encouraged him to express his problems through paintings such as The Maze, which he called a “museum of despair,” and which will later give the title to a film about his life. On the upper left corner of the painting, a woman tied to a pole represents Ukraine, with her religion and culture, about to be raped by the Soviets. The theme of religious and political liberty denied to Ukrainians by the Soviet Union will return in several paintings.

Smith, a fervent Catholic, started to bring Kurelek closer to the faith. His mental condition, however, worried doctors, who in 1953 transferred him to Netherne Hospital, in Surrey. The new hospital was less friendly, and it also made use of electroshock, but William was still encouraged to paint. During the night, at Netherne, he felt he was being visited by “Someone,” while contemplating from his window the gardens of the hospital. Gradually he understood that this Someone—hence the title of his autobiography, Someone with Me—was God. Gradually, he accepted the Catholic faith, which also played a role in his healing.

In 1957, Kurelek received his Catholic baptism sub conditione, since he had already received a presumably valid baptism in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. He started attending the gatherings organized by Father Edward Holloway, the founder of the conservative Catholic magazine Faith.

Curiously, in his autobiography, Kurelek speaks very little about the period following his conversion. It was a period of happiness, featuring a triumphant return to Canada in 1959 and a long honeymoon with his country’s public opinion as a national artist, marriage, children. In 1960, he started his most ambitious project: to illustrate with a series of paintings the entire Gospel of Matthew. He would produce 160 of them, now on display at the Niagara Falls Art Gallery, which opened in 1979 on the Canadian side of Niagara Falls and which also houses Kurelek’s personal archive.

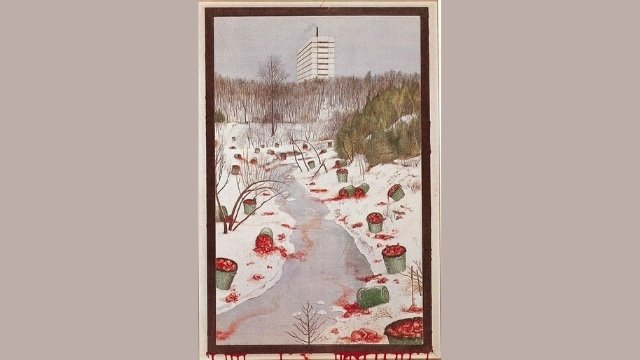

Kurelek got in trouble for his conservative view of abortion and other issues, including his defense of traditional Catholic indictment of homosexuality and his claim that the best thing that happened to the First Nations and Inuit indigenous people in Canada was that many of them converted to Christianity. After, in 1969, Canadian students demonstrated against the massacre of civilians perpetrated in March 1968 in My Lai, Vietnam, by American soldiers and discovered by the press a year later, Kurelek painted one of his most famous works, Our My Lai: The Massacre of Highland Creek, a very strong denunciation of abortion in which a Toronto hospital is the backdrop to buckets full of aborted fetuses and thrown away, while blood drips onto the frame. This is a painting that, in recent years, has often been excluded from exhibitions and catalogues. Undoubtedly, it is a violent painting with an in-your-face pro-life message that some fear may lead to the violence against doctors performing abortions, of which the most radical anti-abortion activists have been guilty in the United States and elsewhere.

On the other hand, as mentioned earlier, with this and other similar paintings Kurelek was also testing religious liberty in Canada. Could admittedly radical religion-based opinions on subjects like abortion be freely expressed in the country? Every time Our My Lai was censored, Kurelek found in the incident confirmation that Canada did have a problem of religious liberty.

There is little doubt that Kurelek sincerely believed in the pro-life cause. When he was diagnosed with cancer, which perhaps he had contracted from the fumes of the spray paint he used, he offered his suffering in reparation of the sins committed against life. He passed away on November 3, 1977.

Kurelek was equally passionate about the cause of religious and political liberty of Ukraine. He prayed and hoped for it, but died before the fall of the Soviet Union. His paintings of skyscrapers and stations blowing up, surprising a world unaware of its own sins, are connected to his apocalyptic side, which drove him to invest in bomb shelters and to predict as certain an atomic holocaust. But they also strangely foreshadowed 9/11.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.