A unique culture is at risk of being lost forever–although it continues abroad, mostly in Israel and in New York.

by Massimo Introvigne

“Bukhara Jews? They’re in New York.” So, before I left for my first trip to Uzbekistan, in 2007, several experts in Jewish history answered my question about one of the oldest and most mysterious Jewish communities in the world. And certainly in New York, the Bukhara Jews are well visible. Several years later, walking down 108th Street in the Forest Hills neighborhood of Queens, I encountered more Bukhara Jews, with their restaurants, stores, music and devotions, than in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. Of some 300,000 Bukhara Jews who still survive in the world (they are prolific, and the number is actually growing), 80,000 are in New York. Another 40,000 are scattered among various cities in the United States and Canada, and 15,000 are in the United Kingdom. 160,000 live in Israel, where many have recently emigrated: but the “Bukhara Quarter” of Jerusalem was formed as early as the 19th century. Some remain, despite everything, in Austria and Germany, and 1,000 in Russia. Nothing remains in France, from where those Bukhara Jews who survived Nazi persecution have almost all emigrated to Israel and America. Nor in Afghanistan, from which the last Bukhara Jews escaped long ago.

And yet the Bukhara Jews are also in Central Asia. In Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, there are only a handful of Jews left, compared to some 15,000 who were still there in 1989. Their ancient synagogue was demolished in 2008 by the government as part of an urban development around the new presidential palace, the Palace of Nations. Interventions by the U.S. State Department and UNESCO only led to the construction of a new modern small synagogue in a different location, but a significant historical monument was lost. And there are Bukhara Jews even in Bukhara.

Many tourists overlook the Jewish connection there of the Magok-i-Attari, the “well mosque,” which is right across the street from one of the hotels built for foreign tourists, the Hotel Asia Bukhara. Local tradition has it that Jews and Muslims shared the same place of worship, whose architecture has something of a synagogue, although there are those who argue that it is an ancient mosque transformed into a place of worship for Jews by some emir of Bukhara who protected them. Others believe that, on the contrary, an ancient synagogue was transformed into a mosque. To be on the safer side, the post-Soviet Uzbek government has converted it into a museum, as it did with many other mosques and madrassas, only a minority of which remain destined for religious use. And the name “museum” for these mosques in Uzbekistan identifies a space where tourists mostly come for shopping, in spaces rented out to sellers of carpets and other objects of the rich local craftsmanship. Orthodox Jews coming from the United States, however, enter and pray. Since they are tourists who carry valuable currency, the authorities turn a blind eye, or maybe both.

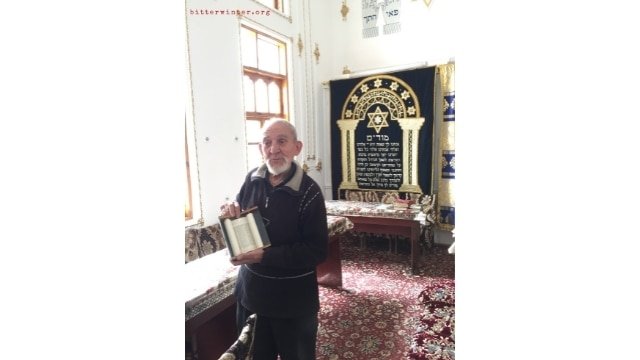

At the edge of the Lyab-i Khauz district, once a “Jewish quarter” but not without mosques and madrassas in the unmistakable Sufi style (today, as usual, “museums”), looking carefully you can also find the real synagogue, a relatively modest structure that has existed since around 1600.

I went there twice. In 2007, I met an old, kind rabbi who died before my second visit in 2018. There were more than 20,000 Bukhara Jews in 1990, 1,000 during my first visit, and 150 when I came the second time.

In 2007, the rabbi proudly showed me photographs of a visit to his modest and poor synagogue by Hillary Clinton, who undoubtedly came all the way down here with an eye on the Bukhara Jews who live in New York. At that time, the rabbi believed that the massive emigration was over, and the community had a chance to survive. In 2018, the Jews I met in the synagogue were not so sure. There is no longer a shochet to prepare kosher meat, nor a mohel to perform circumcisions, although there are enough male Jews to form a minyan and pray communally.

But are the Jews who are left in Bukhara technically “Bukhara Jews”? The answer is, not all of them, but first one would need a definition of what a “Bukhara Jew” is. The question is shrouded in some historical uncertainty. Traditionally, it was believed that Bukhara (Hador) was part of the Babylonian empire, and that those in Bukhara were Jews deported to Babylon who never returned to the land of Israel. Today, many historians doubt that the Babylonians ever controlled Bukhara, and think that Jews arrived there in the 6th century BCE, when the city was part of the flourishing Persian Empire.

It is certain that many Jews arrived in Bukhara in the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, at the dawn of the formation of a “Silk Road” that would last for 1,600 years. These Bukhara Jews largely lost contact with the rest of the Jewish world, only to regain it at the end of the Middle Ages. They thus developed a religious culture, language and music unique in the world. While the ancient Hebrew language was being lost as a spoken language among Jews throughout the world—it would only be restored by the modern state of Israel—in Bukhara, Hebrew was mixed with Tajik to create the Bukhori or Bukharian language, which a handful of Jews in Uzbekistan are still able to speak today.

But the majority speak only or mostly Russian, including the rabbi I once met, and that gave to me as a gift an image of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, while denying that his was a Lubavitcher synagogue. The Bukhara Jews are administratively dependent on the Russian Jewish community, which has entrusted to Lubavitcher rabbis many synagogues, attended, however, mostly by believers who are not part of the movement. And the story is more complex, because there have been Lubavitcher presences among the Bukhara Jews since the 19th century.

While the world’s Jews are divided by ritual and customs, depending on their remote origin from Central Europe or the Iberian Peninsula, into Ashkenazi and Sephardi, the Bukhara Jews are neither, but they have rituals and customs as particular as their ancient language. They are still best known for their clothing, music, and cuisine: although they would now admit that the great “Bukhara Jewish” cuisine today is found mostly in New York. Some Jews who are in the city of Bukhara are not even “Bukhara Jews” but Ashkenazi who came from Russia in different historical periods.

Harshly persecuted by the last Zoroastrian kings of Persia, the Bukhara Jews welcomed as liberators the Muslims, who at least promised them, as followers of a “religion of the book,” the status of dhimmi (second-class citizens, but “protected” and free to profess their religion). And under the Muslims, the Bukhara Jews survived for over a millennium, although there were occasional massacres and forced conversions. The idyllic image of harmony between Jews and Muslims is true only for a few years of the reign of some emirs of the independent state of Bukhara, who willingly employed Jews as doctors, economic advisors and musicians—while other emirs persecuted them on suspicion of being Russian spies.

A court musician of the Bukhara emirs, Levi “Levicha” Babakhan, or Babahanov, became famous in Russia where he died in 1926. But Babakhan is an example of a Jew who had to go through the darkest period in the history of the Bukhara community. During the First World War, Central Asia—including the emirate of Bukhara, which had been under Russian protectorate since 1873—rose up against compulsory conscription in the Tsarist army, and did so in the name of Islam, with massacres of Christian and Jewish minorities. With the arrival of the Bolsheviks, the Red Terror was unleashed against Jews suspected of counter-revolutionary or otherwise “bourgeois” sentiments.

Yet from all this the Bukhara Jews recovered and survived. In the Stalin years, several Bukhara Jews acquired important positions in the government of Soviet Uzbekistan, although this happened only for those who were prepared to hide their religion and their traditions. After the Second World War—in which at least ten thousand Bukhara Jews enlisted in the Red Army died—the religion knew a moment of respite, and in 1945 Stalin allowed the synagogue of Bukhara to be reopened. But the alleged “doctor’s plot” to kill Stalin (1948–1953) involved some physicians who were Bukhara Jews. A harsh repression followed, which was not interrupted by Stalin’s death in 1953.

Only with Gorbachev, manifesting a Jewish identity in Bukhara became possible again, but many took advantage of the perestroika to emigrate. The independent Uzbek state, authoritarian and distrustful of religion in general, has not particularly encouraged Jews to remain in the country. From the 30,000 Bukhara Jews who lived in Uzbekistan as a whole in 1970, the number has dropped to the current 2,000. Yet, some remain. Even in Bukhara—not only in Jerusalem and New York—the last page of a more than 2,000-year-old history has not yet been written.

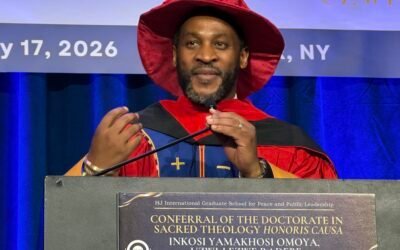

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.