Crusades to ban a literature accused of “brainwashing the masses” show how far faulty theories of mental manipulation could go.

by Massimo Introvigne

In a previous series on Bitter Winter, I discussed how “brainwashing” theories were used to promote certain political ideologies against others (originally, the CIA invented the word “brainwashing” to criticize Communism, and describe what the evil Communists allegedly did), and to discriminate against religions labeled as “cults.”

In fact, some proponents of “brainwashing” theories claimed they were engaged in an epic battle against the “three Cs.” The first two Cs were Communism and “cults.” Almost forgotten is the third, comics. Remembering the era in which “brainwashing” accusations were directed against comics is useful to show that almost everybody and everything can be accused of “brainwashing.”

For a number of reasons, criticism of popular culture as a way of “brainwashing” both children and the working classes into a black-and-white totalitarian worldview focused precisely on comics. Frankfurt School theorists of mental manipulation did notice comics at a quite early stage, and focused their criticism on the two most popular genres in the 1930s and 1940s: superhero and horror comics.

I am interested in this story for two additional reasons. First, I am a lifelong collector of comics, and have contributed a few articles to the growing scholarly literature on the subject. Second, among the comics accused of “brainwashing” their readers were those featuring vampires. I have written extensively on the vampire myth, and have been for several years a member, and the president of the Italian chapter, of the Transylvanian Society of Dracula, which was not a vampire “cult” but an association of scholars studying vampire literature, comics, and movies, as a relevant part of popular culture and of mythologies connected with the supernatural. Many members of the Society were tenured academics. The Society ceased most of its activities in Europe in 2009, when its founder Nicolae Paduraru died, although its North American chapter is still active.

After the early “platinum age” (a prehistory of sort), modern comics were born in the 1930s with the predecessors of the companies still dominating the market today. Superheroes and horror comics were born almost at the same time. Issue no. 6 of New Fun Comics (October 1935) by National Periodical Publications (the predecessor of contemporary DC) featured the first instalment of a story known as “Dr. Occult, the Ghost Detective.” The story is famous for several reasons. It is the first story published in a comic book by Jerome “Jerry” Siegel and Joseph Shuster, the world-famous creators of Superman, disguised under the pseudonyms of Leger and Reuths.

It is also the first horror story, and the first vampire story, in comics history. As the readers would learn in subsequent instalments, Dr. Occult had special powers of his own, and he was in fact the first comic book superhero of the Siegel-Shuster duo. The first villain he met was a vampire. From issue 7 (Jan. 1936) New Fun Comics will be renamed More Fun Comics and it will take two more issues, 8 (Feb. 1936) and 9 (Mar. 1936), for Dr. Occult to dispose of the vampire, and go on to deal with werewolves.

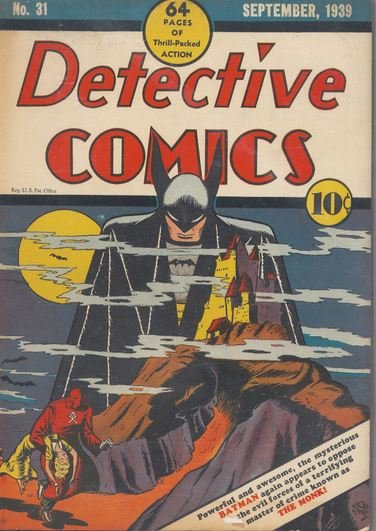

Three years later, Batman himself in its fifth Detective Comics story (issues 31, October 1939, and 32, November 1939) had to deal with a vampire, The Monk, and his female assistant Darla, to save his girlfriend Julie Madison. Batman did indeed have a girlfriend at that time, and as late as May 1997, in no. 94 of Batman: Legends of the Dark Knight, “Stories” by Michael Gilbert featured the same Julie Madison, now an old lady, trapped in an elevator by terrorists and remembering the events of 1939, when Batman saved her from the vampire. In the end, she was rescued again by Batman (who, unlike her, had not aged), confirming that villains such as The Monk, long gone, are never really forgotten in the Batman universe.

For whatever reason, vampires were very successful in comics. A bibliography I, Gordon Melton and Robert Eighteen-Bisang published a few years ago included more than 10,000 English-language comic books with at least one appearance by a vampire, making the vampire the second most featured character in comics history, although a distant second to the superhero.

Frankfurt-School-style comics critics disliked both superheroes and vampires. Superheroes were criticized as quintessential icons of an omnipotent father, playing the same role authoritarian religion, in Freud’s and Fromm’s view, attributed to God. Readers of superhero comics were indoctrinated into the ultimately totalitarian idea that a benevolent supreme power (symbolized by the superhero, but being in the real world the state, the ruling class, or organized religion) will ultimately take care of the job, if only the common folks would learn to leave it to him (more rarely, as in the case of Wonder Woman, to her).

Horror comics, in the late Frankfurt School theory combining class sociology and psychoanalysis, perpetuated the fixation of both children and child-like illiterate working classes into the anal and oral stage of development, with their attending (or at least alleged) masochism and sadism, predisposing those thus indoctrinated both to obey unconditionally the powers that be, and to put their potential for violence at the disposal of the same powers.

Late Frankfurt theorists, thus, developed the core arguments of an anti-comics theory, based on secular arguments of mental manipulation. At the same time, both Roman Catholic and Protestant morality watchdogs (including the Catholic Legion of Decency, originally created in 1933 to lobby against immorality in motion pictures) also focused on comics as pernicious elements of popular culture, for different reasons, branding them as immoral, not respecting the traditional taboos about sexuality and marriage, and conductive to juvenile delinquency. The latter was a point of serious concern for secular critics, too.

Both forms of criticism of comics appeared in the 1930s and in the 1940s, in the U.S. as well as in Europe. However, as in the case of oppositional coalitions against Communism and “cultic” religion, political success could be achieved only through some degree of co-operation between the secular and the religious anti-comic movements. They made strange bedfellows, since their original aims were not the same. Religious crusaders against comics were normally politically conservative, focused on sex and violence, and targeted primarily horror comics. The politics of those influenced by the Frankfurt-School-style criticism were more often of the left-wing type. The allegedly “fascist” superhero comic was seen as a vehicle for “brainwashing” the masses into ideologies of totalitarianism at least as dangerous as the horror comics. Both religious and secular anti-comic crusaders agreed, however, that through comics the masses and the young adults were both manipulated, and adopted the terminology of “brainwashing” as soon as it became available in the political field.

Coalitions were built in several countries. In France, conservative Catholic criticism of comics, whose pioneer before World War II had been Father Louis Bethléem, was substantially translated in their own languages by secular humanists and Communists after 1945, leading to one of the largest anti-comics campaigns in comics history. The situation in Europe (and in some Canadian provinces) was, however, different from the United States. Critics of comics outside the U.S. denounced them as a vehicle of postwar American cultural imperialism, a criticism that conservative religious and political left-wing activists might share.

In the U.S., of course, anti-Americanism was not a factor, but populist opposition to “immoral big business” “brainwashing” the masses for its own purposes plaid very much the same role in building coalitions between religious and secular opponents of popular culture. How this strange alliance worked will be the subject of the second article in the series.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.