Depicted as the quintessential xie jiao, the movement founded in 1986 was eradicated in 1990 and its leader executed. Why do Chinese media remember it now?

by Massimo Introvigne

Once upon a time there was in China a female emperor, Wu Zetian (624–705), the only woman regarded as a legitimate emperor in the history of the country. And once upon a time, but closer to our times, there was another woman who claimed to be the reincarnation of Wu Zetian and founded in 1986 near Anqiu, a county-level city under the jurisdiction of Weifang in the south of Shandong province, a religious movement called the Great Sage Dynasty (大圣王朝). Her name was Chao Zengkun (晁正坤). Her movement was declared a xie jiao (heterodox teaching) by the Chinese Communist Party. Chao was arrested, tried by Weifang Intermediate People’s Court, sentenced to death, and executed in 1990.

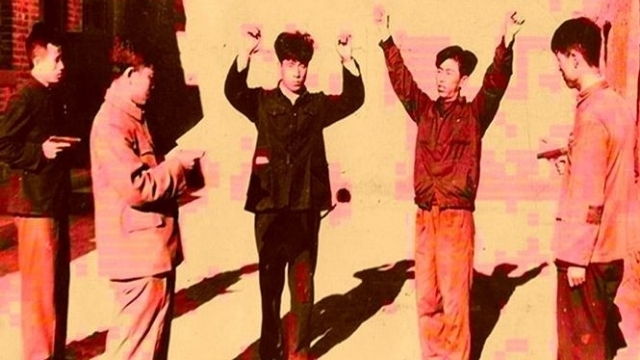

Interestingly, while proclaiming that the Great Sage Dynasty has been consigned to “the dustbin of history” thanks to the swift reaction by the authorities, in 2021, the 35th anniversary of the foundation of the movement, several Party-controlled Chinese media have published articles on it, as they did in 2020 on the 30th anniversary of Chao’s execution. This in turn generated discussions on Weibo, and several rare photographs of the event emerged.

Why this happened is a valid question. One reason is that the Great Sage Dynasty is an almost textbook example of what the CCP, as did Imperial China before it, labels a xie jiao. In her book Mandarins and Heretics (Brill 2017) Chinese scholar Wu Junqing has argued that the Imperial authorities identified a xie jiao on the basis of two accusations: that its leader wanted to challenge the authority of the Emperor and eventually replace him; and that the movement used black magic to bewitch potential followers into conversion (Wu also notes that accusations of brainwashing against contemporary xie jiao are just a secularized version of the traditional black magic narrative).

In this sense, the Great Sage Dynasty was the quintessential xie jiao. Claiming to be the reincarnation of Wu Zetian, Chao wanted to be recognized as empress, and she was accused of having learned black magic from a local Taoist sage and having become a witch. Interestingly, in revisiting the 1990 trial, rather than the modern secularized accusation of brainwashing CCP media accounts still describe Chao as a “witch” (巫婆). They report that Chao was originally a progressive woman, popular in her village because she had some notions of medicine and treated the poor people for free, but she then went astray, befriended Taoist practitioners of magic and superstition, and established first a group called Qinghua Shengjiao (青华圣教) and then the Great Sage Dynasty. She also changed her name from Cao Xiuhua to the more aristocratic sounding Chao Zhengkun.

We do not have any testimony from inside the movement. We cannot hear the voices of the members, and can only listen to the judges and the CCP, who said that some 400 Great Sage Dynasty devotees lived communally, and accused Chao of having established a harem, where she had sexual relations with many male followers. Of course, accusations of promiscuity and sexual abuse are common against leaders of xie jiao.

The judges who sentenced her claimed that Chao’s influence went beyond Shandong, and she had established a “large-scale xie jiao,” with contacts in some 16 different cities. In fact, she was arrested when she was organizing a proselytization campaign in Beijing, which alarmed the authorities. She was executed for “operating a xie jiao and other crimes,” one of the rare female xie jiao leaders to meet this fate. Hundreds of her followers were sentenced to spend time in jail.

Reminding Chinese of her story is a way of reinforcing the stereotypes against xie jiao, and establishing a connection between the Communist representation of evil religious movements and the Imperial one, labeling as xie jiao groups usurping the Imperial authority led by witches practicing black magic.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.